Spring Symphonies: 55/60 - Walton: Symphony No 1

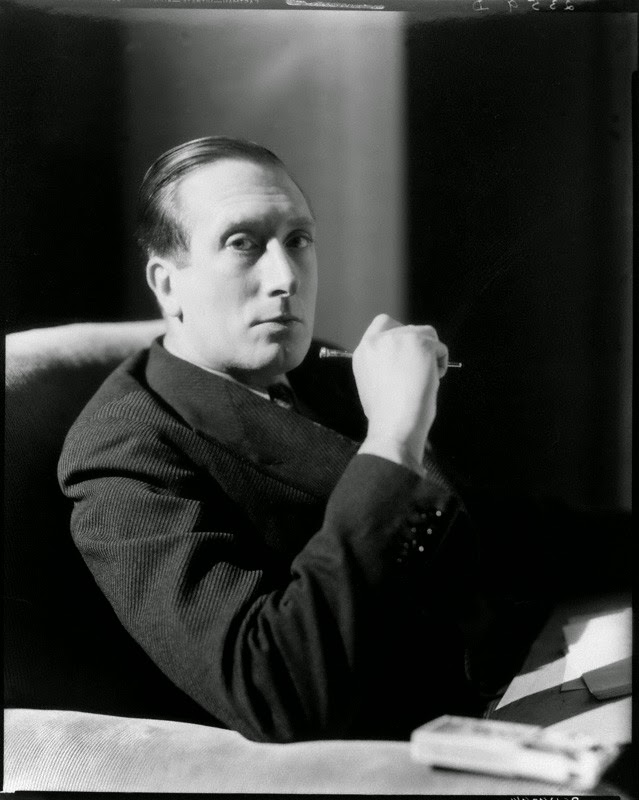

William Walton lived through the most extraordinary times. He was born in 1902 in Oldham in the industrial hothouse that was the North West of England and he died just short of his 81st birthday on the Mediterranean island of Ischia in the house he’d had built there. In his youth he was marked as the successor to Elgar and yet to some of his younger contemporaries his music was too backward looking. There are some who say that having made enough to retire to the sun his creativity dried up and that he under-achieved. This charge is perhaps too easy. His two symphonies, numerous orchestral works, chamber works, film music and operas make a formidable body of work and even if we don’t quite see their merits immediately his style is recognisable and throughout he was a strong presence in English musical life.

He was privileged in what could now be called soft networks on management circles throughout his early life. On the basis of his experimental String Quartet of 1921 - Alban Berg took him to meet his teacher and king of the new musical world, Arnold Schönberg. He met Stravinsky and Gershwin, was taught by Ansermet, travelled Europe and met everyone who was anyone in the English musical scene including Elgar. Beyond music he was in a world of literary London at a very exciting time through the Sitwells - though Noel Coward walked out of the first performance of his ground breaking entertainment Façade. Much is made of his youth - an Oxford undergraduate at 16 years old, one wonders if he was over-cooked by this environment. His First symphony should certainly count as evidence of that - but seems to point both ways.

Much of the attention on this symphony focuses on it’s change in character - from a most forceful and exciting, if not scary first movement to a finale which is certainly majestic and ardent. There are those who will argue that this reflects Walton’s writers block in late 1933 when his love affair with Imma von Dörnberg ended (she walked out) and in 1934 when his next affair with Alice, Viscountess Wimborne began. The first three movements in the bag by 1933 the symphony wasn’t finished until 1935 and premiered by Hamilton Harty and the BBC Symphony Orchestra in November 1935. It was picked up pretty rapidly - and is still regularly played. The Berlin Philharmonic gave it an outing in 2011 under Semyon Bychkov - a strong advocate of the work. Karajan even conducted it in Rome in 1953 (though he cut it and restored it).

Every time I listen to it I think it’s a symphony, and there are too many of these, that stands really on it’s first movement and doesn’t really cohere or amount to much more than the first movement alone. But others will find more in it and enjoy the last movement for it’s over the shoulder look back at Elgar. Walton was perhaps covering his bases given Elgar had died in 1934 and was much mourned.

Every time I listen to it I think it’s a symphony, and there are too many of these, that stands really on it’s first movement and doesn’t really cohere or amount to much more than the first movement alone. But others will find more in it and enjoy the last movement for it’s over the shoulder look back at Elgar. Walton was perhaps covering his bases given Elgar had died in 1934 and was much mourned.

The opening of the symphony is one of the most sophisticated and effective an Englishman has every written. The music starts with low quiet drums and then a horns in stages and a quick impatient rhythm on strings. The oboe of the top gives us a theme and then the strings and section by section wind and brass drive the music forward over a wonderful rhythmic tapestry. In the right hands and at the right speed the twitchy, angry fiery scoring can lose its way but with a properly assertive conductor this can sound and feel like a forest fire. If Walton’s passions were being stretched and tested during the time of writing, I don’t think we’d be at all surprised.

The movement contains some wonders of concentrated orchestration and relentless propulsion and the excitement and tension builds throughout to a point where it plateaus on broad chords - hammering out the movements motto. The energy seems spent. A whole symphonies worth of power seems to have been expended and yet we’re less than halfway through the movement. Walton introduces slow music of a mysterious flavour - all of it is familiar but fragmented and distorted. The strugglee to recombine these pieces has a Promethian strength behind it, and once the order is restored, a fantastic panorama opens up building to a climax that is straight out of the Late Romantics. The coda bustles though some exciting transitions but never losing the underpinning energetic life force. And slow the struggle wheels into a triumphant conclusion after an titanic sense of opposing forces is resolved. It is one of the most telling movements in all of the many great English symphonies - and maybe the best thing Walton wrote for orchestra for the thrill seeker.

The Presto scherzo that follows is marked con malizia and in the context of a relationship breaking down we can all imagine a good deal of domestic turmoil here. In purely musical terms it seems to flit between the styles of Stravinsky, Copland, Roussel and Hindemith with no hesitation. And it has the kind of clarity which Prokofiev might have envied. It is certainly full of vehement outbursts and like it’s predecessor is unrelenting. And there is no softening Trio. Its a piece of extreme point making perhaps.

The slow movement has much of the feel of the French style (perhaps Honegger) as it starts - it is positively languid. And I think we momentarily search for something a bit more pointed after being taunted for two movements. There’s an underlying tension in this movement too, it emerges slowly. The harmonic underpinning is unsteady, the woodwind interjections are inconclusive and directness to a certain extent. Occasionally we get a first movement motto - a dropping figure - coming through. There may be sadness under these unsteady and unsettling passages. It marked Andante con malinconia but it is surely more than that. The point making seems to be overdone for me here. One wonders what the audience at the first performance of these first three movements (the finale wasn’t ready) made of this. It tails off - it’s unclear where the audience is left in this maelstrom.

The finale - which took so long - is completely foreign to what has gone before. It starts in Elgarian fanfare mode. The theme is then energetically thrust forward - this has a much brighter disposition. The fugue that breaks out has a real swing and a full-bodied energy. It’s hard to think of this music being by anyone else. There’s a softer passage which is full of optimism from a very different place to the preceding movements. There’s a toccata like style to the passages and the forward momentum is more like driving an open topped sports car down country lanes than the juggernaut of the first movement.

One gets the feeling about 7 minutes in that Walton could maintain this sweet and energetic invention all night, it’s not note spinning per se, but it a long way from the terse point making in the first half of the symphony. The coda goes on too long and uses too many familiar devices even down to a trumpet solo (a la Vaughan Williams though faintly jazzier). There’s a whiff of distant forgotten harmonies which is welcome but the composer doesn’t bring the parts together in a convincing way for me. The Siberian ending of chords is just a bit obvious and long overdue.

So I end up recommending this symphony for it’s many virtues which are mostly loaded into the first two movements and the first movement which has a venom few have equalled. As for the rest see what you think.

Here’s Bychkov in the first movement - you can find the rest of this performance if you survive this rollercoaster :-) -

Comments