Spring Symphonies 50/60 - Shostakovich: Symphony No 8

|

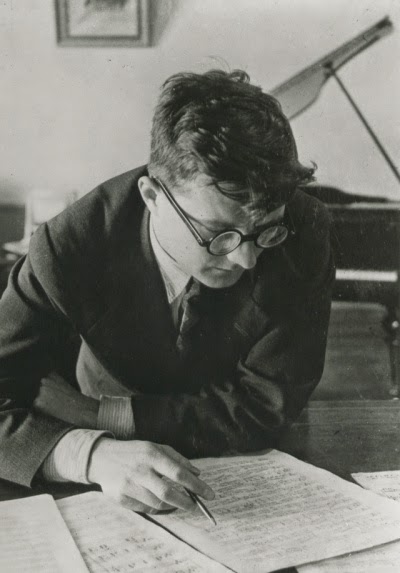

| Shostakovich - Library of Congress 1942/3 |

I had a rather odd experience last year when after hearing a performance of the Fourth Symphony by Shostakovich I realised I had a Shostakovich problem and I needed to start again. In short I don’t think I was listening deeply enough to Shostakovich’s orchestral music. When I started to listen to the symphonies again from the point of view of the suppressed Fourth Symphony I began to realise how much more there was to the composer and how much I had missed.

In truth I ought to write the Spring Symphonies entry on DSCH 7, the Leningrad Symphony again having listened to it and it’s symphonic companions many times during last winter. Maybe I will one day, but for now I have two admissions firstly that I now get Shostakovich and his musical language more than ever before, and second I hold it very dear and I’m still finding great wonders in it so I really struggle to find words which encapsulate it and struggle too to find a symphony to write about…

In truth I ought to write the Spring Symphonies entry on DSCH 7, the Leningrad Symphony again having listened to it and it’s symphonic companions many times during last winter. Maybe I will one day, but for now I have two admissions firstly that I now get Shostakovich and his musical language more than ever before, and second I hold it very dear and I’m still finding great wonders in it so I really struggle to find words which encapsulate it and struggle too to find a symphony to write about…

I have chosen the Leningrad’s successor, the Eighth symphony - largely because it becomes a bigger symphony each time i listen to it. It becomes a better symphony each time and it is a significant symphony in it’s historical background. It was written in 1943 and first performed in November of that year under the baton of the iconic conductor Evegeny Mravinsky. It was not well received and was eventually banned by “committee” between 1948 and 1956. More striking to think of the tone of this work compared to compositions of that year such as Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra (which satirises Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony) and Vaughan Williams Fifth symphony (that national idyll in time of war). For Soviet artists the end of the turmoil was to be a long way off.

The symphony begins with chords as stark as those which end Sibelius’ Fourth but much more emphatic. The tensile shrill passage which it announces is on the very edge of scraping our nerves. The effect is harrowing and cumulative especially as the dark chords keep making appear again and again in the background. This movement is long and arduous and so a detailed description would be similar. It morphs very slowly into a nihilistic march with this material at it’s root. There’s something very mechanical or in human about it. The composer take step music to great heights and depths, he moves it faster and about half way through (13 mins in) the woodwind forces - which are extensive - 4 flutes (3rd and 4th doubling piccolos), 2 oboes, cor anglais, 2 soprano clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon). They spiral round on each other in a way that becomes very claustrophobic until Shostakovich pulls the movement into a series of immense climaxes. The mood there after is breathless both in speed and utterance. Until a bigger and more apocalyptic climax thwarts all progress - it’s repeated three times. A cor anglais takes up the progress - it is melancholic and tremendously exposed, the music sinks to a dead calm stillness and even as it rocks itself into a quiet calm the brass awaken it. The final minute is repetitive and yet strangely soothing whilst retaining an edge. It is though the dragon has gone to sleep. The final chord is exquisite.

The next movement - even after a break - is a shock to the system. This is a tumbling march which has at it’s core driving elements which the first movement lacked. It serves as a kind of scherzo. The pointed writing gets more energetic as the movement progresses. It has a strained busy-ness and enforced grandeur that you might say are both aspects of the regime in wartime Soviet Russia. The heroism of the Seventh symphony seems a degree more convincing than what we have here.

The next movement - even after a break - is a shock to the system. This is a tumbling march which has at it’s core driving elements which the first movement lacked. It serves as a kind of scherzo. The pointed writing gets more energetic as the movement progresses. It has a strained busy-ness and enforced grandeur that you might say are both aspects of the regime in wartime Soviet Russia. The heroism of the Seventh symphony seems a degree more convincing than what we have here.

The third movement is something of a shock again - a forte toccata based on a long rhythmically uniform melody passed from one section of the orchestra to another. The interjections become more pressing as the music goes round and round. It has monolithic quality - crushing even. More Scherzo-like than it’s predecessor, the “headache” effect subsides into circus music for solo trumpet and percussion - it is in context ludicrous. More so when the toccata starts up again. It perhaps owes more to the Fourth symphony (which at that time was suppressed) than many realised at the time. It builds to a migraine inducing climax with more of the hideous crunching tutti chords. But these chords are not an ending.

The chords and the new atmosphere are the beginning of the fourth movement, a Largo, built on the passacaglia form (roughly define as variations over a repeated baseline which itself may be varied). This movement is so very quiet and gentle it is hard to place it in this work of big and ugly gestures. The variation element gives continuity, but as it progresses there is very little light shed on it’s darkness. At halfway through the dropping bass figures feel my like tears than salve. The solo horn plays a melody which is emotionally static. The whole discourse has lapsed into one of great sadness and hopelessness. The simmering flutes are a measure of this deliberate lack of distinction. A sadness of the war still being fought - many would say that it is more than that. It is nihilism, that haunting hopelessness about all situations. These are in many ways beautiful figures that the woodwind weave but they hold no defence for the viciousness which has proceeded this music. The landscape is barren and wreck and Russians who supported the Revolution must have been wondering about their fate after long years of battle.

Again the music slides from one movement to another. A hesitant but noticeably upbeat bassoon leads the music to a sunnier place - or seemingly so. The marking Allegretto is at least lighter. The tone picks up and the music fairly dances along. I think it’s only right to mention Shostakovich’s mastery of ambiguity here (though it’s been apparent since his music took a turn in Lady MacBeth of Mtsensk). So what we have here is somehow always going to have a double or triple meaning. Out of the blue that dance becomes a dance macabre - swirling but with nod back to Romantic composers and their interest in such things. The music burrows down in a self indulgent repetitious loop - so much of this symphony is about repetition and its grisly inward looking feeling. These episodes stifle change, except in this one where the bass leads a charge to a sunnier aspect. Fanfares usher in a challenge to the squeaky winds. There is truly some optimism here - a true turning C minor into something better and victorious. But the struggle continues - out of the blue the hammer blow chords return - three of them, echoing their appearance in the first movement. This doesn’t seem to be Germany field guns either. This assault ends in a return to the unruly solo fiddle in macabre view.

There’s a gentle section which offers some succour, the comfort on offer seems distinctly wet, the strings drawer the movement to a close. But Shostakovich does not stop here. Instead the music meanders down to a different place. In the quietness the voices are thin and trembling. The tread is repeated and haunting. The end comes like a passing into unconsciousness, the music just loses all will to be awake…..or is that alive. It is uncompromising, bleak and horribly prefigures the mood in Soviet Russia after the war under Stalin. Shostakovich might have been writing for himself - his struggle continued, for his artistic friends - many of whom were compromised one way or another or for his people, who’s glorious heritage was undergoing State rehabilitation. We will never know. It is an ending which haunts you once heard - it is a symphony that never prepares you for it’s journey or finds another way no matter how much we might want it. It is a symphony which isn’t about love or war or London or the Sea. I think it is an unexpurgated examination of fear.

There are many musical questions we can delve into about the nature of ambiguity, the violence of some bits of this work and the banality of others. It is a symphony we might expect to end in glorious victory, even if that victory is imagined. But it doesn’t and that will keep us talking about it. writing about it and listening to it avidly.

Petrenko is perhaps it’s greatest advocate at the moment and his recording on Naxos is well worth hearing but here is Haitink with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in a live recording:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6RwGIoms1Y

There are many musical questions we can delve into about the nature of ambiguity, the violence of some bits of this work and the banality of others. It is a symphony we might expect to end in glorious victory, even if that victory is imagined. But it doesn’t and that will keep us talking about it. writing about it and listening to it avidly.

Petrenko is perhaps it’s greatest advocate at the moment and his recording on Naxos is well worth hearing but here is Haitink with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in a live recording:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6RwGIoms1Y

Comments